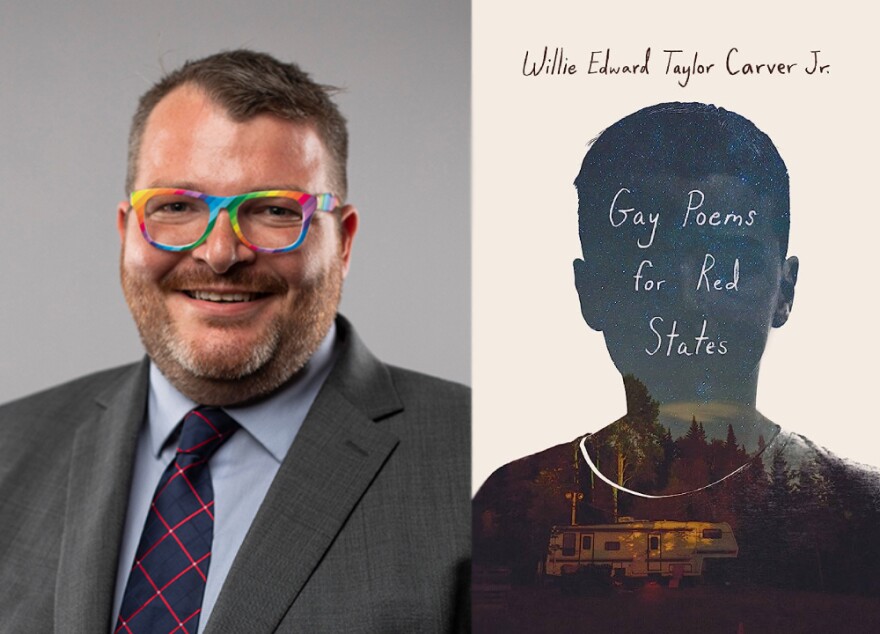

Willie Carver Jr. was named Kentucky Teacher of the Year in 2022, but a lot has happened since then.

The openly gay educator quit his job teaching English and French in Montgomery County last summer, citing LGBTQ discrimination. And, just last month, he published Gay Poems for Red States – his first book of poetry. Now Carver is speaking out and advocating on behalf of the state’s educators and queer youth.

WKMS News Director Derek Operle sat down with Carver earlier this month.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Derek Operle (DO): First off – so nice to meet you. I finished the book last night. It was great, man. It's always so moving to hear and read about that kind of experience here in your home state because you know it happens. Talk to me about your youth – a lot of this book pulls from your experiences growing up.

Willie Carver Jr. (WC): Thank you. So I grew up in Appalachia. I was from Floyd County, Kentucky. I think in rural southern places there's a lot in common pretty much anywhere you go. So I know that anyone reading is going to recognize what it's like to have really hard working parents, but to also say you come from poverty.

It's not an indication of how hard people work. It's an indication of the circumstances. But, Appalachia also has some distinctions, particularly how people talk. Some cultural aspects, I have some 150 first cousins, I would say 80% of them live within 20 minutes of me. So family was kind of everywhere, family was important. In a lot of ways it was a really good childhood, but I think I probably shared this with most people who grew up in the 80s and 90s. For a queer kid, it was not good.

DO: [In some of your poems] you write about having to move schools, you write about not being able to afford to rent a trombone. How did your family's financial situation impact you growing up?

WC: I think there's always that comparison that kids make, like, that I was the only one getting the trombone repossessed in my mind. As you get older, you realize there were probably other people who didn't dare try to even get the trombone, right? So you realize that your experience was a little more universal. But I certainly grew up feeling like “there are people here who are going to do something, and then there's me, like, I will never be the kind of person who has a trombone, I'll never be the kind of person who has good things and gets to hold on to them.”

I think people really underestimate what that does to the psyche of kids. When I think about the students I had, yes, teaching French and English was the official primary goal. But my primary goal was to make them dream, to make sure that they understood what they could do. I don't want to take away how hard it's going to be for them compared to other people, but if we just say, “Well, it's hard, don't try them” … what are we doing to them?

DO: You talk about some formative experiences in your book. Your first crush, realizing that you can make a classroom a safe space for yourself, your grandmother’s biscuits, and realizing that you wanted a different toy at McDonald's. How did those experiences coalesce for you in this book?

WC: I've been thinking a lot about what causes a person to write. How do you know what's going to be a cohesive collection or set of experiences? For me, there was a kid in me. I went through some particular trauma the last year that I was a public teacher. [The kid in me] was so angry. I actually sat down to write an angry email to my superintendent, because I saw so many students who were just being thrown to the wolves for political reasons. And I instead wrote the poem about my toy at McDonald's.

I didn't know it was gonna happen, but I think this little boy, who is still in me somewhere, he grew up thinking he would never really get the choices he wanted. Whether we're talking about queerness, whether we're talking about being Appalachian and having a different accent or whether we're talking about poverty … what we're really talking about is people who do nothing wrong, who just exist but, by virtue of existing, are limited. All of these are structures that give some people autonomy and take it from other people.

Whether we're talking about queerness, whether we're talking about being Appalachian and having a different accent or whether we're talking about poverty … what we're really talking about is people who do nothing wrong, who just exist but, by virtue of existing, are limited. All of these are structures that give some people autonomy and take it from other people.

I think, somewhere inside of me, this kid was sort of putting it all together. This book is an angry response to that, but also a reminder that different circumstances don't necessarily have to mean different results.

DO: This is your first published book. Did you start writing poetry when your Kentucky Teacher of the Year sabbatical started?

WC: Because I was a teacher, everything I did was teaching. It was really rare for me to explore something just for me. I pretty much spent my summers and my weekends thinking about my classes and what the kids might need. So even the poetry that I wrote would be to fill gaps that they didn't have.

Students need teachers who can be vulnerable. We ask them to write this essay … where are we writing essays? We ask them to write a poem … but are we writing poems? So I would always do the work for them. It's weird. I guess there had always been this intended audience, which is people who needed help, my students who I did all my writing for, and suddenly I didn't have students.

I think what sets teachers apart as a general rule from a lot of other people … is that the sudden lack of work becomes really stressful because they identify as a human being, as someone whose purpose is to help. When I left the classroom, the walls disappeared and the whole world became my classroom. And so I looked out at this state and thought “how many people can I try to write a poem for?

DO: The message that you always tried to distill down for your students turned into one that you just needed to write down to get out.

WC: The message is … take life less seriously so that you can take seriously what's really important. We would do this dress up show in French class, so it's kind of goofy on the surface. We learned vocab words for clothing, and how to talk about what you're wearing, but then I would bring in this giant bag of clothes – just random sun hats and skirts – and encourage them to dress in any weird way possible. And then we created a runway and they would walk the runway seriously but not seriously.

The goal was to feel brave enough not to care what other people thought because getting trapped in needing to be what other people want you to be is the surefire way to prevent an Appalachian kid or a queer kid or a poor kid from really succeeding. I can't force every Kentuckian to play dress up, but I'd love that.

DO: You have a poem in here about watching Jerry Springer with your father and what happens in this “very special” episode is that there was a young man and his father struggling with the young man’s coming out as gay. You wrote that your father said if he had a son that wanted to say something like that, that he hoped you knew it’d be okay. Tell me what happens next.

WC: Flannery O'Connor says that, basically, Christ is the ghost that haunts the South. There's this sort of ghost of religion that's hanging over you and in a lot of ways, people just don't question it. They might actively do things that go completely outside of what the Church says, but they still offer some semblance of respect to it. We went to church. My mom took it very seriously. My dad did not. But I heard what gay people were in church.

I heard the preacher talk about what monsters they were. For me, I didn't know how to be gay and not be a monster, and also did not want to let them down. Both of my parents had been let down a great deal in their lives. I didn't come out at that moment. It was in college, when I took my same angry Appalachian approach and applied it to my queerness. I said, “Well, I'm not going to come out because nobody else has to.” So I just suddenly was living my life as openly as possible.

My dad asked, directly, I think it was on my 21st birthday, if I was gay. And I said, “Yes.” And he said, “Well, I'd rather you not be.” And I said, “Well, me too. But here’s where we are.” And then we both laughed. And then he said, “You feel pretty deeply, and that's good. But you're gonna have to walk into every room, the rest of your life and assume that you're just as good as everybody else.” And I really took those words to heart, because I knew he saw what I needed. And he wanted to give me that lesson.

DO: A couple of different teachers make appearances in your book. There’s one educator who helps you get through some tough times when you changed schools, there's another that leads you through what you thought was finding a dinosaur skull that turned out to be a horse skull. What influence did your teachers have on your life?

WC: School is magic. I think we take it for granted because it's a universal experience. It's also everyday, but the everyday can be magical and I think that's the magic that's hard to see. I remember being in kindergarten and walking into this orderly place. I lived in chaos and so everything there was routine. But, more importantly, I would walk in and this teacher would look at me and see a version of me that could make the sound “buh” and say and spell with a letter B. Someone looked at me and said, “This person is going to be able to do math,” right. And they basically did spells and then I would walk out literally more powerful than I was when I walked in. That was always school.

For me, it was this transformative place where someone saw multiple versions of me and helped me build towards them. Schools are the heart of communities, and it is the only place that can catch society's problems. There's no other place, really, that does it for children. When we didn't have food, school had food. When we didn't have heat, school had heat. When we didn't have water, school had water.

These are still problems that students face, and there are no other structures catching them. There was no question – [teaching] was what I was always going to do. And when I won Kentucky Teacher of the Year … I started naming my teachers. My kindergarten teacher just wrote me … to tell me she had just purchased my book. And I said to her, “Wow, every letter I use in this book you taught me.” How powerful is that? Talking about seeing what someone might be?

DO: What was your experience like teaching in Montgomery County? That’s a pretty conservative part of the state, more than 70% of the votes cast there in the 2020 presidential election were for Donald Trump.

I think we sort of get in this idea like, “Oh, we're in the south, therefore this will happen.” So the good people don't really fight back because they assume it's inevitable because it's all they've ever known.

WC: It was a very conservative place, but I actually really fell in love with the teaching experience. Like once the doors were closed and I was teaching my classroom, the kids were ready to learn. They were excited. And I could see those transformations in them. The families were great.

The majority of the parents were excited to see their children learning and respected education as a concept. I really loved that about where I taught. I taught for some of the most homophobic people I've ever met, though. And I learned that there's a small contingent of my town that is really racist and really homophobic, and those people make a lot of noise. I think we sort of get in this idea like, “Oh, we're in the south, therefore this will happen.” So the good people don't really fight back because they assume it's inevitable because it's all they've ever known.

It's all they've ever known that of course, we're not going to read a book by a Black author. It's all they've ever known that of course, we're not going to have an openly gay teacher. What drives me is that I think there is a holy charge to care for these young kids, all of them. And what I saw over and over were administrators who were willing to sacrifice certain students for political expediency.

There was always this sort of threat of emotional harm, and I would always fight back. It was 10 years of fighting – and winning – because I knew the law. But the last year, things are so toxic, that these were now rising to physical safety issues, and the schools were still refusing to care. And that's when I said, I can't be a part of this. And I know that there are teachers who are there who are fantastic human beings who are still fighting. I think, for me at that moment, I couldn't keep doing it and look myself in the face. I think queer teachers right now are really seeing so much hatred.

[Almost] every single rural queer teacher I know has quit. I think I can think of well, I can think of one person who hasn't. I really wanted to tell a story that resonates for them to remind them who they are, to remind myself who I am. We've got to make sure that these young people see versions of themselves. And that's what's really troubling about all of these LGBTQ teachers having to leave the classroom … because it's too big of an ask. I want to tell the story of LGBTQ youth, even though I'm not an LGBTQ youth, it's because (1) I do have those memories and (2) it's too big of an ask to tell these kids to tell their stories right now. And I think teaching as a rural queer person is too much for anyone really right now to go through. For those who are doing it, I'm so glad. I'm so happy for those who are able to find safe spaces to do it. I'm so glad and I'm going to keep fighting for those spaces to exist, but it is very hard right now.

DO: Your book came out in June. Your sabbatical’s over. Now you’re working with the University of Kentucky. What's next for you?

WC: There's this, like, exponential rise in opportunity for me now. And I'm just going to say, “Yes.”

I'm working with a lot of nonprofits at the moment and I'm really excited by the nonprofit sector because the truth is even higher ed is in danger from extremism, as we're seeing in Florida. So I think being a part of a group that doesn't have to enforce racism, for example, would be nice. Right now I'm working with the Kentucky Youth Law Project. We help any LGBTQ youth under the age of 25 who is encountering legal issues for free. [I’m also working with] the Rainbow Youth Project out of Indiana. Their mission is just to help LGBTQ youth. They connect young people to counselors who otherwise couldn't get access to them.

So definitely some advocacy work. I'm doing a lot of speaking these days, as well. I think something I learned from this book is our stories will heal – and not just us. They're going to help other people. I really want to talk to people, especially LGBTQ people, about finding ways to access their own story. So I want to do some work helping people heal themselves.

DO: Willie, thanks so much for taking the time and talking with me.

WC: Oh, thank you for having me. It's absolutely an honor.