This article is part of a special series produced by Murray State University students participating in an investigative reporting fellowship partnership with WKMS.

Instead of the hustle and bustle you’d expect to see when Kentucky’s legislative representatives come to town, lawmakers reported a strange, quiet echo through the halls of the state Capitol during this year's legislative session.

“Normally the hallways are flooded with people who are coming up to lobby their government and to express what they want to see happen,” said Democratic Senator and minority floor leader Morgan McGarvey of Louisville. “It’s hard to even walk down the hallways or find a seat in the annex cafeteria around lunch time.”

Not this year.

“That’s gone,” McGarvey added. “The people aren’t there.”

Despite the empty hallways, McGarvey said lawmakers were busier than ever as they flocked to Frankfort for the 30-day 2021 General Assembly.

Lawmakers had to craft a budget, a task usually reserved for even-year sessions which are twice as long, as well as grapple with high profile issues such as impeachment and coronavirus response, all while access to the Capitol was limited by the coronavirus pandemic.

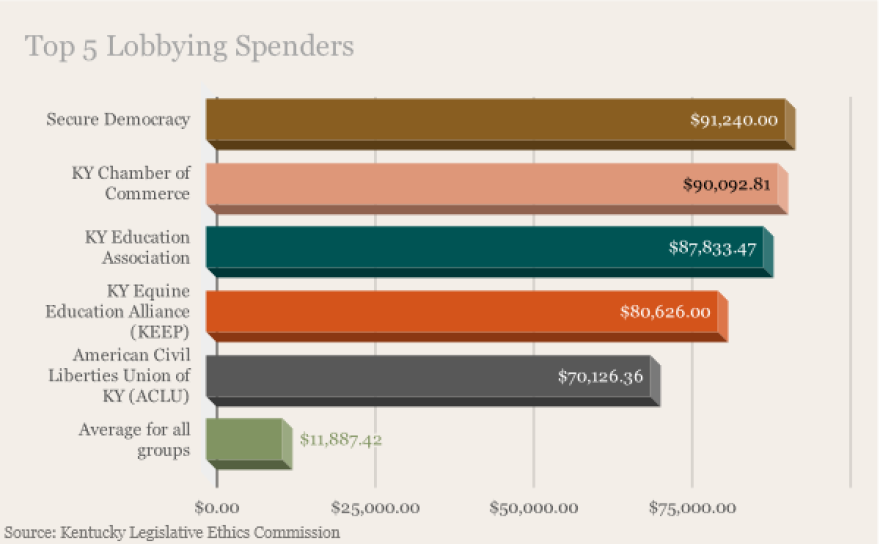

While there were fewer faces in the hallways, lobbyists still spent hefty amounts of money to make sure their priorities were met. Organizations with business before the legislature must report their spending to the Kentucky Legislative Ethics Commission. They spent more than $4.4 million lobbying during the 2021 session as of Feb. 28, according to the most recent reports available.

Big spenders included Secure Democracy, a nationally-focused advocacy group that came to Kentucky to push for election reforms such as expanding early voting and absentee ballot access, and several of the most influential groups in Kentucky politics such as the Kentucky Chamber of Commerce, representatives from the horse racing industry, the association representing Kentucky teachers and the ACLU of Kentucky. Three of the top five lobbying spenders disclosed more than $152,000 spent on food and drinks at a time when the state’s public health officials have discouraged large gatherings.

An in-depth inquiry by the WKMS investigative reporting fellows indicates expensive lobbying campaigns appear to have paid off. Lawmakers' priorities during the 2021 General Assembly largely reflect those of the most well-connected and well-funded lobbyists. Those priorities include protecting businesses from tax increases and coronavirus liability, as well as limiting the governor’s powers during an emergency.

In a year when access to the legislative process has been severely limited, lobbyist Ronny Pryor, who represents clients such as Kroger and the Kentucky Hospital Association as president of Capitol Solutions LLC, said those who succeeded are those who already have a direct line to lawmakers.

“How well you’re doing right now depends on, to a great extent, how good is your contact list in your phone,” Pryor said.

Republican Rep. Jason Nemes of Louisville said the idea that people would be limited by who they already know reflects the reality of government, and was not exacerbated by the pandemic, though the virus did mean less face time with citizen advocates.

“It’s always a tiered system,” Nemes said.

Republicans are largely in control of the legislative process due to their current residence as the supermajority party in Kentucky’s legislature. However, no member of the Republican leadership nor their spokesperson responded to multiple requests for comment.

Narrow Goals

The unique constraints of the 2021 General Assembly took root almost a year prior, when the coronavirus abruptly cut short the 2020 legislative session.

The legislature typically passes a two-year budget in even-numbered years, when sessions can stretch for up to 60 days. But Lawmakers only passed a one-year budget last year. They had to complete the cycle during this year’s session, which was half as long.

So as this year's session began, lawmakers anticipated spending much of their time negotiating the budget, which McGarvey described as “Kentucky’s ultimate policy document.”

With so much going on, some organizations with legislative interests lowered their expectations of what would get done, Julie Denton said. Denton was a Republican state senator from 1995 until 2015 and now represents clients such as the suburban fire departments in Jefferson County, Kentucky Organ Donor Affiliates (KODA), Pearl Medical and other Louisville-area outfits.

“People tried not to do anything they didn’t have to do for this session, from my clients’ perspective,” Denton said.

The legislature passed what Shively Democratic Rep. Joni Jenkins called “almost a shell budget” in January, but then Jenkins said budget talks faded into the background.

“We really came into this session anticipating that’s what we’d be talking most about and that hasn’t really happened,” Jenkins said.

In the meantime, the Kentucky legislature got to work passing other bills. They quickly passed two bills restricting abortion, and four bills restricting the governor’s emergency powers. One of the abortion-related bills became law without Governor Andy Beshear’s signature.

Lawmakers were able to override Beshear’s vetoes to codify the rest into law. The next bill enacted into law redefined electronic gambling systems at horse tracks and was signed into law on Feb. 22. Other pieces of legislation touching on important issues languished in legislative limbo.

Examples of legislation that did not move past the committee stage include a bill addressing maternal health, one expanding voter registration, and two attempts at curbing no-knock warrants.

As a result of the Republican majority many Democrat-introduced bills encounter difficulties gaining attention during the session.

“Traditionally, the House Democrats have been in favor of raising the minimum wage and we’ve done some workplace safety bills,” said Jenkins, but those bills have not made progress this year. We continue to push and continue to work really hard, and build those relationships across the aisle when we can.”

Off to the Races

When it comes to bending the ear of Kentucky lawmakers, money talks.

The groups that spent the most money lobbying in the first months of the year had their goals met, with some having their wish lists granted by the midpoint of the session.

One big ticket item that passed with bipartisan support was a package to expand voting access and election security. Secure Democracy spent more than any other lobbying group in Kentucky from January through February, to push for what it calls common sense voting laws, such as expanding early voting to three days before election day.

Beshear signed that voting package into law on April 7.

Sarah Walker, the executive director of Secure Democracy, said the majority of expenditures reported in this session were from polling Kentuckians and research, and were not spent directly on lobbying efforts with lawmakers.

As a non-partisan, non-profit advocacy group operating nationwide, Walker said the pandemic changed the way Secure Democracy reached lawmakers. Before COVID-19, the group had a dedicated team on the ground in Kentucky to arrange meetings and communications between the top brass and lawmakers. In this session, the group relied on data and written communications because they were not able to meet with lawmakers face-to-face.

“Normally, we'd be going into the state houses and having multiple one-on-one conversations and having them over time and repeatedly,” Walker said.

Walker said pre-existing relationships with lawmakers were more important than ever this year when they were unable to stage more visible advocacy tactics such as filling the halls with volunteer advocates.

The Kentucky Chamber of Commerce spent just over $90,000 lobbying during that time frame, including $21,800 buying food and drinks for lawmakers, according to lobbying disclosures.

The Kentucky Chamber of Commerce footed the bill for some lawmakers' dinners at a virtual banquet in February 2021 that featured some of the most influential people in the commonwealth.

In attendance were Gov. Andy Beshear, Speaker of the House David Osborne, Senate President Robert Stivers, as well as Jenkins and McGarvey. Sponsors included Fidelity Investments, and alcoholic beverage companies Beam Suntory and Brown-Forman, among others.

The Chamber supported unemployment insurance reforms such as protecting businesses from tax hikes and using federal money to replenish the unemployment insurance trust fund included in two bills that eventually became law. The Chamber also supported a bill protecting businesses from coronavirus lawsuits that needs Beshear’s signature before Saturday to become law.

Kate Shanks, vice president of public affairs at the Chamber, said coronavirus restrictions have introduced new challenges, but the Chamber has been able to reach lawmakers.

“I don’t think there are legislators that are using this opportunity to avoid constituents or advocates because they don’t want to talk to them,” Shanks said.

An instructive example of the legislators’ priorities was Senate Bill 120, which protected one of Kentucky’s key industries and championed by the Kentucky Equine Education Alliance (KEEP), one of the legislature's highest spending lobbying organizations. Other groups that stand to profit from the legislation spent money lobbying as well, including Keeneland and Kentucky Downs race tracks.

The bill was introduced on Feb. 2 by State Senator John Schickel, a Republican from Union came in response to a Kentucky Supreme Court ruling in September of 2020 that questioned the legality of certain gaming machines in horse racing parlors across the state.

The Historical Horse Racing (HHR) machines look and play similar to slot machines, but odds are based on horse races of years past. Kentucky’s constitution prohibits any form of gambling except the kind used to place bets against other gamblers at horse tracks.

The Kentucky Supreme Court’s decision put the wheels in motion. Even before the session began the Kentucky Equine Education Alliance (KEEP) began working with lawmakers to work out a deal, according to Elisabeth Jensen, the executive director of KEEP.

“We worked from the beginning to have it done very quickly,” Jensen said. “We wanted to make sure that we didn't leave anything to chance, that we reached all the legislators so that we got it done and in time to get to the governor as quickly as possible.”

The legislation passed and was signed by the governor on Feb. 22, just 16 days into the legislative session. KEEP reports spending more than $54,000 on food and drinks that same month.

Lawmakers passed the legislation despite criticism that the arrangement shortchanges the state by taxing the machine’s profits at a lower rate than traditional slot machines. Kentucky taxes HHR machines at a rate of 18% while only about 8% of that goes back to the Kentucky general fund. Neighboring states Ohio and Indiana tax similar gaming systems at 33.5% and 40%, respectively.

When Senate Bill 120 passed the senate and moved to the Kentucky House of Representatives, the tax issue threatened to stall the legislation that was otherwise moving at breakneck speed.

As a compromise, race tracks wrote a letter to lawmakers promising to study the tax issue and address those concerns.

Louisville Democrat Mary Lou Marzian was skeptical that the industry will follow through on this promise.

“We all know that when you don’t want to pass a bill, you create a task force. It’s really what you say you are going to do when you know you’re not going to do it,” Marzian said at a legislative hearing in February before eventually voting in support of the legislation.

A separate bill to raise taxes on Historical Horse Racing Machines did not earn a hearing or a vote.

Outside Looking In

Citizen advocates are typically a fixture in the statehouse, but this year, people representing grassroots causes such as poverty relief had to get creative in order to get lawmakers' attention.

Groups who previously would rally large crowds to the Capitol to get lawmakers’ attention or show up at committee hearings couldn’t rely on such tools this year.

“We went to the Capitol [before COVID-19] and we were able to do it in the annex building and do it in person, which was good because then you can go and talk to the legislator while you're there,” said Rev. Amanda Groves, president of the Kentucky Council of Churches and activist with the Kentucky Poor People’s Campaign and West Kentucky Chapter of Kentuckians for the Commonwealth.

This year, Groves said, “We have to think outside the box because we don't have access to committee meetings and we can’t see them face-to-face.”

Kentuckians for the Commonwealth, one of the better-funded progressive organizations in the state, reported spending $10,700 on lobbying in 2021 so far. The Kentucky Council of Churches, the organization Groves leads, reported spending just $180.

Whereas the Chamber of Commerce hosted lawmakers with a corporate sponsored dinner, the organizations with which Groves is affiliated had to do more with less.

Groves took part in a wheeled protest outside the capitol on March 15 to advocate in support of National Poor People’s Campaign’s 14 demands, which included equitable access to COVID-19 testing and vaccines as well more money for safety net programs.

A line of vehicles, decked out in signs listing the 14 demands, circled the state capitol three times, becoming more spirited each time with honks, waving flags, and shouts. Protesters finally congregated on the steps of the Capitol to sing, speak, and pray, using a portable microphone to address lawmakers who were looking on.

The protest appears not to have swayed the lawmakers: None of their demands became law, plus lawmakers rolled back SNAP food assistance for children.

Groves believes face-to-face contact might have helped stop the SNAP legislation from becoming law.

“We [KCC] opposed it and spoke out, but it would have been nice to have been there in person with our stoles and collars to remind them of the moral implications of their decisions,” Groves said.

Transparency

Some lawmakers said visitation limits at the capitol came at the expense of transparency.

As in previous years, Kentucky lawmakers used amendments and committee substitutes to replace bills with new language during the legislative process. This year, however, fewer people were watching.

Committee substitutes are proposals offered by a committee as replacements to an original bill already being considered during the session and can be proposed and voted on within the same day.

Republican Nemes said committee substitutes submitted during previous legislative sessions would be reviewed by lobbyists, activists or other interested parties in person while the committee was in session.

“That was very difficult, because those folks, the hospital association, for example, they didn’t have ready access to the committee substitutes,” Nemes said. “So while the rules didn't change, people not being able to be in the building had a tremendous impact.”

Normally, amendments must be filed 24 hours before the legislature votes on a bill. This year, leadership frequently suspended rules surrounding amendments to allow bills to pass in a significantly limited time frame.

Jenkins said the practice was “troubling” and could make it seem like lawmakers were “trying to sneak things through from the public.”

“I’m not saying they’re doing that, but I’m saying it gives you that feeling,” Jenkins added.

Jared Bennett of the Kentucky Center for Investigative Reporting contributed to this report.

Murray State University's Journalism and Mass Communications department and WKMS News collaborated to create an investigative reporting fellowship program in partnership with the Kentucky Center for Investigative Reporting. Four Murray State students dedicated a semester of learning to the program. This article is a product of that learning experience.